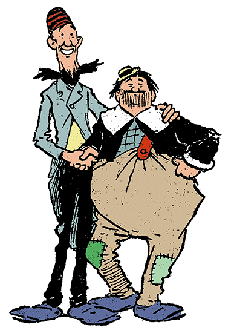

“World-famed tramps” Weary Willie and Tired Tim – adapted from a drawing by Tom Browne, 1898

There were unsavoury characters galore in early British comics. In cartoons and comic strips, readers were confronted with the capers of layabouts, drunks, the idle poor, the idle rich, thieves, scroungers, cheats, mashers, urchins, pawnshop scrooges, a startling array of bone-headed foreigners, and tramps – plenty of tramps. To exaggerate slightly: the earliest tramps either pursued their selfish aims violently, or were roughly chased away as a threat to society, or both. The occasional tramp strips in Comic Cuts in 1892-93 display viciously poor taste: a tramp has an epileptic fit in a tailor’s establishment (a visual pun on the word “fit”); a tramp is eaten by a hungry dog; a tramp forces a masher to give up his clothes by threatening to put his eyes out; a tramp takes the crutches off a disabled man for “spoilin’ my business” (Comic Cuts, 25 February 1893). Their very names reflect these vagrants’ wretched existence: Jaded Jabez, Dismal Dick, ‘Ungry ‘Enry, Mildewed Mike, Pinching Pete, and so on (characternyms from The Funny Wonder). Such a cruel portrayal of the tramp doubtless did little to encourage reader identification and enhance sales, and none of these tramps became regular characters in the comics – until 1896.

It was Nottingham-born artist Tom Browne who broke the tramp mould. Prompted in part by the sight of two down-and-outs on the Thames Embankment, also inspired by Don Quixote (probably the edition illustrated by Gustave Doré), Browne created two amiable characters he called Weary Willie (or Willy) and Tired Tim for Harmsworth’s comic Illustrated Chips in 1896. One thin tramp (Willie) plus one fat tramp (Tim), bold, brazen and wily, constantly in scrapes in a win-one lose-one rhythm, they exude confidence and cheerfulness. In a late-nineties strip, Willy and Tim breeze into view like working-class flâneurs, strolling round the city, their city, observing, commenting, and intervening at whim (see Illustrated Chips, 1 October 1898, B3).The popularity of the series was “instant and enormous”, practically doubling the sales of Chips (Bell 1899: 227; see also Johnson 22). By the time he retired from the comics after a decade of prolific activity, not only had Browne changed the template for tramp portrayal in the comics – and the imitations, some by himself, were numerous – by common academic consent he had also been hugely responsible for the consolidation of the style of British comics (Gifford 1984: 20–21; Sabin 1993: 20; Gravett and Stanbury 19). His “world-famed tramps” continued to decorate the cover page of Chips every week until 1953, drawn by various hands, for the last forty-four years by Percy Cocking (Gifford 1987: 237).

Some of the other characters entering British comics at this time can only be described as zany. Many of them were invented by Irish artist and painter Jack B. Yeats, beginning with his “Adventures of Chubblock Homes and Shirk, the Dog Detective” (1894–97), a title humorously embodying multiple references: the popular Sherlock Holmes stories then appearing in The Strand Magazine; the strong locks made by the Chubb Lock Company, locks which also feature in Conan Doyle’s fiction (see “A Scandal in Bohemia”); also the Chips serial “Dirk, the Dog Detective”. Yeats had a penchant for creating oddballs. Besides his Chubblock, this exhibition has reproductions of a handful of his odd characters: rough-and-ready repair man and inventor The Handy Man (created in 1897); unsuccessful American trickster Hiram B. Boss (1897); cunning crook Ephriam Broadbeamer, “Pimply-Nosed Smuggler, Pirate and Other Things” (1898); odd camel Fairo the Second (1898); weird robot Who-Did-It (1907); and winged avenger Dicky the Bird-Man (1910). The web list of comic strips Yeats invented between 1893 and 1917 is incomplete (irishcomics.wikia.com), while a catalogue of his pen-and-ink drawings and illustrations merely mentions them en passant (Pyle 21 and 24), thus placing him in the company of many early British comics artists whose work has been neither fully recorded nor adequately examined.